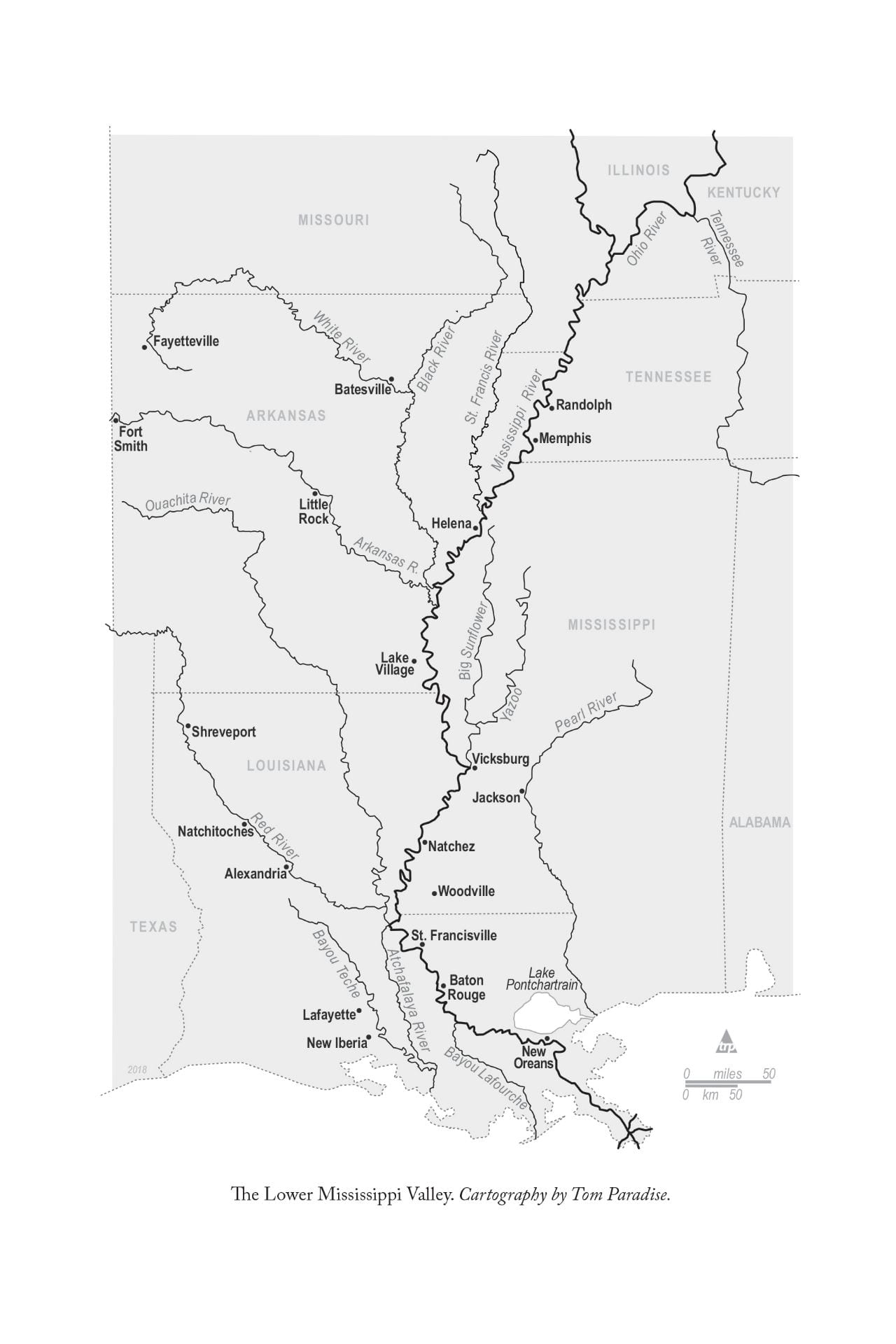

During the antebellum years, over 750,000 enslaved people were taken to the Lower Mississippi Valley, where two-thirds of them were sold in the slave markets of New Orleans, Natchez, and Memphis. Those who ended up in Louisiana found themselves in an environment of swamplands, sugar plantations, French-speaking creoles, and the exotic metropolis of New Orleans. Those sold to planters in the newly-opened Mississippi Delta cleared land and cultivated cotton for owners who had moved west to get rich as quickly as possible, driving this labor force to harsh extremes.

Like enslaved people all over the South, those in the Lower Mississippi Valley left home at night for clandestine parties or religious meetings, sometimes “laying out” nearby for a few days or weeks. Some of them fled to New Orleans and other southern cities where they could find refuge in the subculture of slaves and free blacks living there, and a few attempted to live permanently free in the swamps and forests of the surrounding area. Fugitives also tried to return to eastern slave states to rejoin families from whom they had been separated. Some sought freedom on the northern side of the Ohio River; others fled to Mexico for the same purpose.

Fugitivism provides a wealth of new information taken from advertisements, newspaper accounts, and court records. It explains how escapees made use of steamboat transportation, how urban runaways differed from their rural counterparts, how enslaved people were victimized by slave stealers, how conflicts between black fugitives and the white people who tried to capture them encouraged a culture of violence in the South, and how runaway slaves from the Lower Mississippi Valley influenced the abolitionist movement in the North.

Readers will discover that along with an end to oppression, freedom-seeking slaves wanted the same opportunities afforded to most Americans.

S. Charles Bolton is professor emeritus of history at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and the author of several books on colonial religion and early Arkansas.

“S. Charles Bolton’s deeply researched and elegantly written account of runaways in the lower Mississippi Valley provides a valuable corrective and joins recent scholarship by Fergus Bordewich, Larry Rivers, and Matthew Clavin in demonstrating the regional and temporal variations in describing flights from slavery. … Bolton’s rich, illuminating account should be consulted by any teacher or researcher interested in the numerous varieties of fugitivism.”

—Douglas R. Egerton, Journal of American History, March 2021

“Fugitivism enriches scholarly knowledge and understanding of enslaved fugitives and fugitivity in the antebellum South, introducing individual stories of fugitivity from the lower Mississippi River Valley. It makes an original contribution to the historiography by offering new perspectives and information that are sure to generate scholarly discussion, especially around the concept of fugitivism and its use in distinguishing resistance to slavery from acts of self-actualization waged by enslaved persons.”

—Shaun Wallace, The Journal of Southern History, May 2020

“…a magisterial meditation on escape from the Lower Mississippi Valley. … By retraining our eye from the macro—the slave system being resisted—to the micro—the experiences of individual, idiosyncratic escapees—Bolton uncovers a history of flight so directionally and motivationally varied as to defy simple categorization. Sometimes escape approximated a choice with ‘the pull of self-actualization and anticipated happiness’ as important to an escapee as ‘the push of exploitation’ (p. 8).”

—Kathryn Olivarius, Environmental History, April 2020

“With profound insight and deep research, Fugitivism is a brilliant and comprehensive analysis of the role of escaped slaves in Louisiana and the Lower Mississippi Valley. It reveals complexities and nuances of the common practice of ‘running away’ and demonstrates how the violence of capture and punishment shaped the national discourse on slavery, freedom, and abolition. Bolton’s book is exquisitely researched and thought-provoking in its account of the diverse experiences of fugitive slaves and their impact on the South and the nation.”

—Urmi Engineer Willoughby, author of Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Chapter 1 – The Honest Growler and Absentee Slaves

Chapter 2 – Like Ants into a Pantry

chapter 3 – I Had Rather a Negro Do Anything Else Than Runaway

Chapter 4 – De Boat Am in De River

Chapter 5 – The Urban Runaway

Chapter 6 – Stealing Slaves to Sell or Save

Chapter 7 – Each One Is Made a Policeman

Chapter 8 – Federal Fugitives, the Kidnapper Captain, and Gruesome Stories

Postscript

Appendix

Notes

Bibliography

Index