Wilma Rudolph was born on this day (June 23) in 1940.

Born and raised just about forty miles east of Nashville, Tennessee, in the small town of Clarksville, Rudolph was the twentieth of twenty-two children born to Blanche and Ed Rudolph. Her father worked as a railroad porter and picked up odd jobs around town to supplement the family income. Like most African American women of that period, Blanche Rudolph found work cleaning the homes of Clarkesville’s white families. Similar to Coachman, Rudolph remembers her father as a strict disciplinarian—“he ruled with an iron hand”—and her mother as a person of strong faith.

As a child, Rudolph endured a host of illnesses. When she was not suffering from scarlet fever, pneumonia, or whooping cough, a common cold would keep her ill for weeks. Moreover, she had a twisted leg with a foot that turned inward, a condition her mother attributed to being born with polio. Regardless of the specifics, it is clear that Rudolph spent most of her early years in the house ill rather than running and playing

with the other children. Due to her poor health, she did not begin attending school until she was seven. By that time, she had been wearing a brace on her crooked leg for two years to help keep the leg straight during the day and to facilitate walking.That crooked leg and the associated treatments to straighten it defined Rudolph’s childhood, and the brace marked her as different from the other children. “Psychologically, wearing that brace was devastating,” she recalled in her autobiography. By the time she was six, Rudolph was traveling twice a week by bus with her mother to Meharry Medical School in Nashville for additional treatments designed to strengthen and straighten the leg.

For four hours each visit, she would endure the same regimen as doctors would poke, prod, and examine the leg; string it up in traction; place her in a steaming hot whirlpool bath; and, finally, massage the twisted leg. When she returned home following the hour bus ride, Rudolph would race to her bedroom to examine the leg in the mirror, hoping to see some visible improvement. In between the hospital visits her mother would perform exercises and apply heat, thought to be one of the key treatments for healing. Although the treatments were difficult, Rudolph recalled that the bus rides to Nashville opened her eyes to a bigger world, giving her a thirst for something beyond the small town of Clarkesville. Moreover, she credited the struggles she underwent with her leg and her other childhood illnesses with creating the competitive spirit within her that paid off years later when she entered athletics.

The trips to Nashville lasted four years, until Rudolph was ten. She continued wearing the brace on and off for two more years, generally when her leg ached or she needed the extra support. Finally, when she was twelve, her mother packed up the brace and sent it back to the Nashville hospital. In Rudolph’s words, she was “free at last.” A new chapter of her life was about to begin. Confined to the house as a young child and limited by a leg brace through adolescence, Rudolph now longed to become involved in the childhood activities that she had missed. Basketball, in particular, captured her attention. At the start of seventh grade, she entered the newly completed Burt High School, a secondary school for African American children covering grades seven through twelve. The girls’ basketball team was open to students in all grades, and Rudolph’s older sister Yvonne was already a member of the team. This was a definite advantage, not only with Coach Clinton Gray but also with Ed Rudolph, who liked his children doing things together. “He had this thing about family togetherness,”

Rudolph remembered about her father, “so he told my sister, ‘Yvonne, you take Wilma along with you to play basketball, you understand?’” Basketball worked well for the younger Rudolph who was still trying to strengthen her weakened leg. She could limit her running, playing a game where she pivoted, passed, and waited for shots. She tried out for and made the team but, as a seventh grader, spent the year on the bench. She used her time wisely, however, learning the rules of the game, observing how effective rebounders positioned themselves, and studying how players drew fouls while shooting.

Rudolph made the basketball team the following year but again experienced only limited playing time. She thought she might get some playing time as an eighth-grader but it was not to be, and she still felt that the coach only accepted her onto the team because of her sister. Coach Gray did put her in a few times during the season, but only for a minute or two at the end of games that the team was winning by large margins.

The most important thing that year happened at the end of the basketball season. Coach Gray announced that he was planning to resurrect the girls’ track team, and he invited the basketball players to try out for it. Rudolph did, more to have something to do in the spring and to stay in shape for basketball than for any love of track. While it was not clear at the time, she had found her athletic calling.

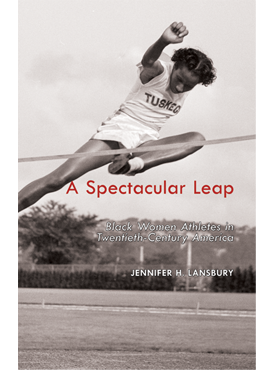

From “Foxes, not oxes”: Wilma Rudolph and the De-Marginalization of American Women’s Track and Field from A Spectacular Leap.