REMEMBERING MILLER

Although I’d stumbled along as a poet for almost twenty years by the time I attended a 1979 writers conference in Little Rock, my real career in poetry began that summer day on a bumpy station-wagon ride with Miller Williams and Jim Whitehead. I had just heard their dazzling talks about poetry, we were in transit to some conference event, and by the time our ten-minute chat was over, I’d decided to apply for the MFA in Creative Writing program at the University of Arkansas.

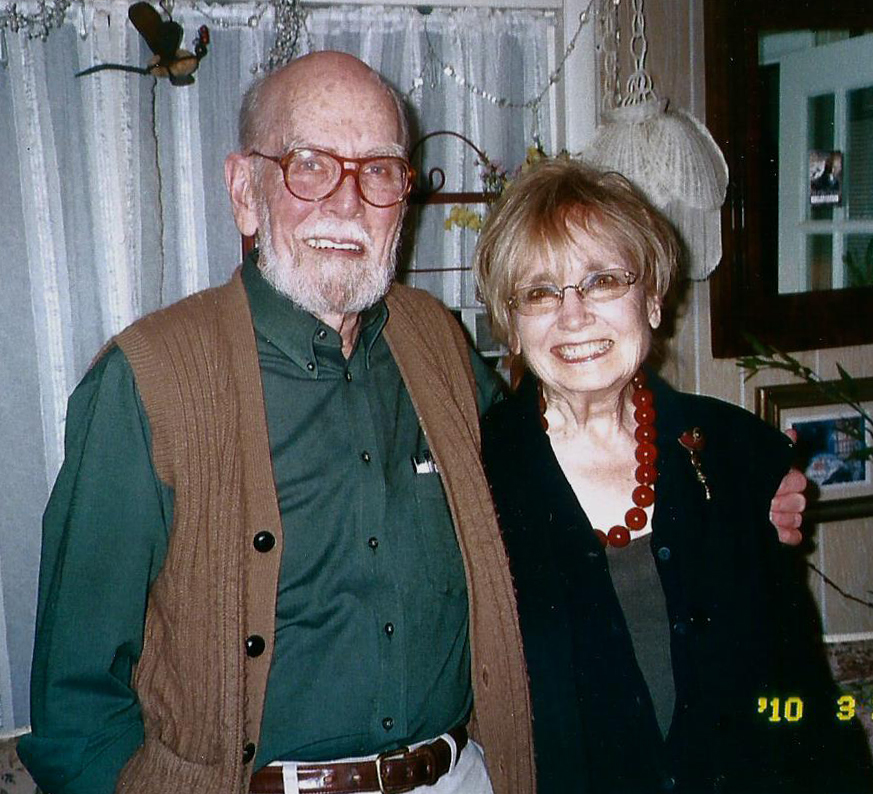

Miller became my advisor and teacher, then my editor and mentor, then, after I graduated from the program, a close friend. He and his wife, Jordan, and I and my husband, Charles, spent many an hour in the Williams sunroom discussing Ciardi or Yeats or the reasons pick-up trucks are displayed on Arkansas front yards. It was a professional and personal relationship that was to last 35 years, until his death.

Miller was a marvelous poet of international renown, a genius teacher, and a dedicated writer. Once, while an MFA student, I asked Miller if he planned to attend a university play that evening. “No,” he said. “When I’m not teaching, I’m writing.” That day I learned about discipline and focus.

Miller was a workhorse, as noted in his New York Times obituary. I was present when he started the University of Arkansas Press from the MFA lounge in what is now Kimpel Hall, with a make-shift desk, a part-time secretary, and tireless zeal.

He was a gentleman—courteous, witty, with a thaw-an-igloo smile. And he was self-deprecating. He would often say, after expounding on poetry or life, “Well, that was nothing you asked and more than you wanted to know.” It was, of course, never more than I wanted to know.

One of his top admonitions about writing poetry was, “Cut the fat—the bones are what last.” He also believed that poetry should appeal to “squirrel hunters as well as professors,” having somewhere in it “the smell of the possum.” He abhorred the obtuse, noting that a poem should be readable—“clear and mysterious at the same time.”

He wrote poems of great depth, irony, and heartbreak, as in “Showing Late Symptoms She First Tries to Fix Herself in the Minds of Her Children,” but he could also laugh at himself in his poems. Philip Martin in his brilliant essay-obituary of Miller in the Arkansas Democrat- Gazette, quotes from a Williams poem, “My Wife Reads the Paper at Breakfast on the Birthday of the Scottish Poet”: “Poet Burns to Be Honored, the headline read. She put it down. ‘They found you out,’ she said.”

I can only imagine that Miller had in mind Jordan and his own breakfast table when he wrote the poem. Whether or no, it is my privilege to have known the man and the poet, to continue to count his beautiful and caring wife as my friend, and to have sat a few times at that table.

—Jo McDougall

Jo McDougall is the author of four books with The University of Arkansas Press. Towns Facing Railroads: Poems (1991), From Darkening Porches: Poems (1996), Daddy’s Money: A Memoir of Farm and Family (2011), and In the Home of the Famous Dead: Collected Poems (2015).